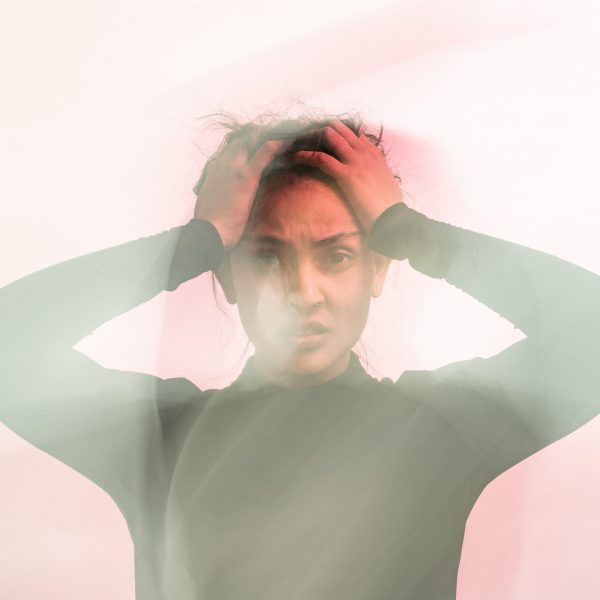

Untangling brain clutter by removing distractions can enhance cognitive ability.

It's 9pm. As I pull the sheets back and climb into bed my mind is still, happy. I didn't do much today. Just a few months ago I would have felt guilty. A chronic maximiser, I measured success by the number of activities I'd managed to complete that day. I'd pile into bed exhausted but satisfied that I'd used up the capacity of my waking hours.

I'd pride myself on staying on top of emails, Facebook and the news. I have two children, aged nine months and three, and a new business, Zambesi, aged one.

I travel a lot and sometimes experience the sensation of "skimming" the world.It feels, or felt, productive.

I began to question this approach. Reflecting on the past few years, I realised I had generated a massive amount of activity but didn’t have much to show for it, except wrinkles. I had done lots of stuff, but was it the right stuff?

One of my most successful friends, Amanda, has built a global e-commerce business based in San Francisco. Amanda isn't a cartoon entrepreneur who runs around trying to do lots of things at once. She pauses before answering a question and she speaks slowly. Amanda has never had a parking ticket. When I visit her house she apologises for the lack of furniture. There's no clutter and no television.

I wonder how much Amanda's clear house and clear mind contribute to her success. She seems to achieve so much, yet never appears busy; she is always calm, focused and happy.

At the start of 2019 I recognised I needed to remove a lot from my life. But before making these big changes, I consulted Dr Penny Van Bergen, associate professor of educational psychology in the department of educational studies at Macquarie University. Is Amanda just born perfect or could I increase my capacity and improve my health by doing less?

"Brain clutter is caused by two things: multitasking and too much stimuli in the environment," says Van Bergen. "It’s clear that the more someone multitasks, the less they’ll be able to focus. It's natural to want to skim Facebook and the news and take in lots of small bits of information in a passive way because it’s easy. It's a bit like eating junk food.

"Your working memory is what you use to concentrate, to make decisions and to be truly productive. If you overload your working memory with random information and distractions, then it'll fire off in lots of different directions and drain your resources."

I asked Van Bergen for some advice on which distractions to remove to enhance my cognitive ability. Here's what I tried:

The news and Facebook: I used to always have ABC News on in the background. It felt important. But I found myself worrying about different news stories throughout the day. When I reflect on all the hours I've invested in keeping up to date, I find it hard to think of anything I've gained. I used Facebook to keep across the activities of my social group, but I barely know most of the people in my feed. No one benefits from my worrying about news stories or monitoring my social network. It all has an impact on my cognitive load.

Junk: We recently moved to a new house, which was an amazing opportunity to get rid of junk. We organised a council pick-up and ruthlessly disposed of clothes, linen, furniture, books, CDs and loads of things we didn't use and didn't need.

Van Bergen suggests that physical clutter also affects your ability to concentrate. "If you have stuff lying everywhere, your brain will kick into gear to try to manage it. You'll subconsciously be thinking you should do this with that."

Events and meetings: I once invited Amanda to meet a prominent politician, but she declined. She wasn't "taking external meetings" that month. I wish I could be so focused. I have managed to restrict external meetings to two days a week, and I work from home two days, which reduces personal preparation and travel time. I seem to get so much more done on these days.

We recently moved suburbs so we could reduce time spent commuting. We put our TV in a small room (not the lounge) so there’s no background noise in the house.

I expected that making these changes would give me more time. But I didn't realise how much more productive I’d become or that I’d feel so much happier and calmer.

Van Bergen says: "It's very easy to fall into the trap of engaging shallowly with the world: taking in lots of information and doing lots of things. It feels easy and simple, but it's not satisfying. Ultimately, removing distractions and focusing on one task at a time will be more productive, more creative and more satisfying."